Speculations about Genomic Features of Asexual Animals

Published:

About a month ago we have posted a preprint to bioRxiv about genomic features of asexual animals. We found plenty of cool things I will try to summarize here the main points and mostly do the speculations that were too bold for the manuscript.

The idea behind this study is to

- avoid conclusions derived out of a single lineage, because every single species is weird in some sense and it’s just impossible to tell the difference between lineage specific evolution and a general consequence of asexuality.

- avoid comparing methodological biases. Looking at the same thing with a different microscope might create a difference that is not really there. We wanted to unify “the microscopes” as much as possible so we have reanalyzed ploidy, heterozygosity and TEs using methods1 based on raw reads, not assemblies. In this blog I will talk exclusively about heterozygosity and genome structure.

With such a great setting we found genomes of 24 different asexual species that available.

| Analyzed species | Cellular mechanisms of asexuality |

|---|---|

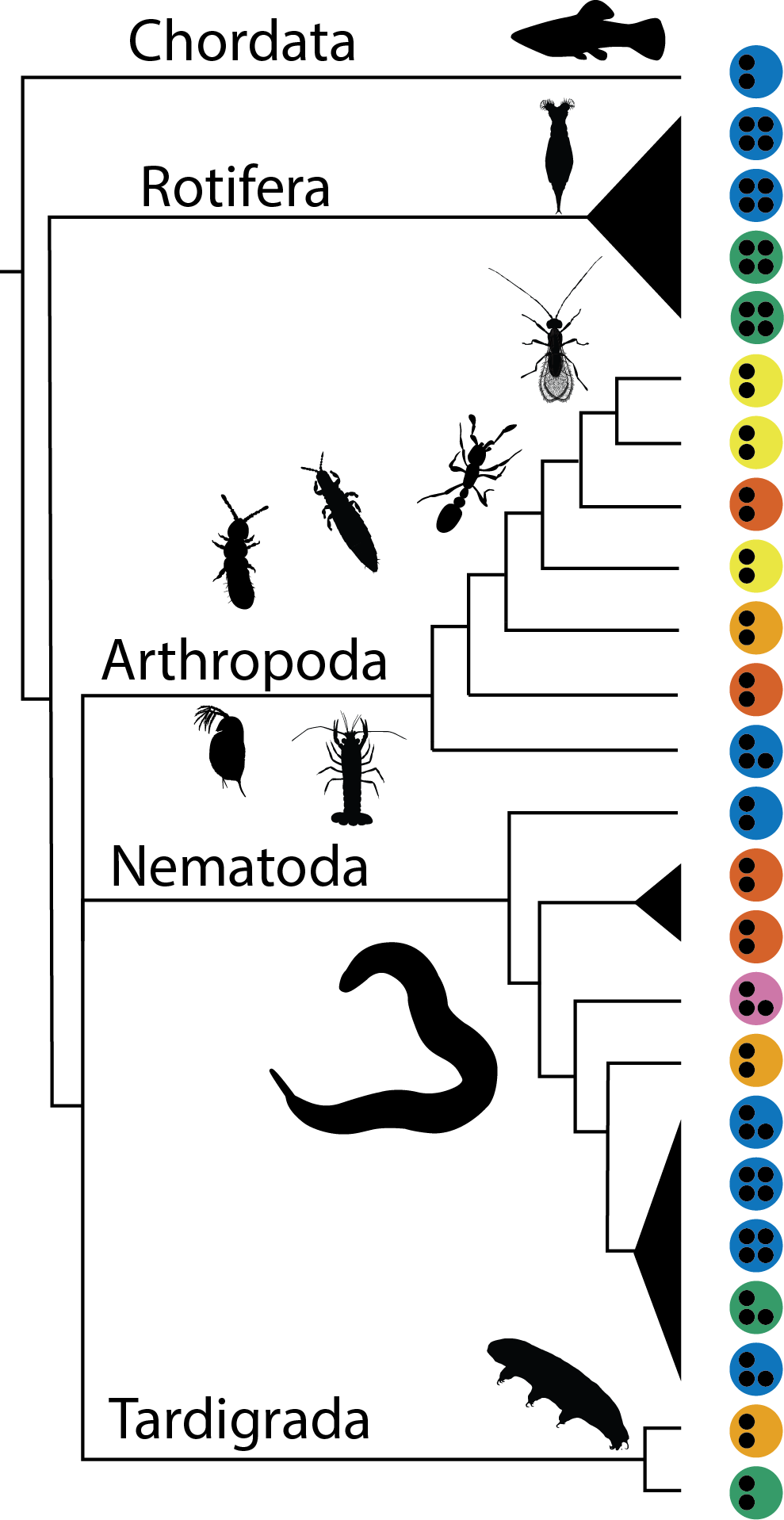

|  The analyzed species varied greatly in cellular mechanisms of asexuality (colour); ploidy levels (the black points) and origin of asexuality (not in the Figure). The black triangles are possible single origins of asexuality The analyzed species varied greatly in cellular mechanisms of asexuality (colour); ploidy levels (the black points) and origin of asexuality (not in the Figure). The black triangles are possible single origins of asexuality |

Heterozygosity

Using argument of Birky 1996, assuming negligible amounts of gene conversion, old mitotic “blue” asexuals are expected to carry a lot of heterozygosity bacause of mutations independently accumulated in both (all) of the haplotypes. However, we found no such pattern. Instead of that, all the variability of the dataset was explained by the hybrid origin - regardless of the cellular mechanism. The heterozygosity is shown on the next Figure using the same colour scheme and categorization by origin of asexuality

Fascinating, there are at least three species that should lose heterozygosity over time due to recombination during meiosis. Diploscapter pachys, D. coronatus and Panagrolaimus davidi (the two orange and the pink dots on right up). Assuming that literature is right about them being meiotic asexuals there is only one possible explanation - they do not recombine (or recombination is rare and only at the sides of the chromosome(s)2. However, why they don’t recombine? Maybe it’s just the divergence of haplotypes that physically prevents the recombination. However, this would not explain how comes that all of the hybrid asexuals are heterozygous. My speculation is that these are actually f1 hybrids, they carry full gene sets of both parental species, any loss of heterozygosity must be a process deleterious to fitness. Now imagine the freshly founded asexual population where a small fraction of individuals have lower recombination rates than others. Selection will select for lowly recombining individuals because their offspring will just do better than offspring of happily recombining competitors. So I suspect that recombination will just very fast get selected out.

This ideas are sort of consistent with hybrid zones of sexual species. F1 crosses hardly ever show any lowered fitness in comparison to parents, it’s backcrosses that are crewed up… But unlike sexual hybrids, asexual do not have to backcross and therefore I see there this open space for selection against recombination.

So why are there asexual is no heterozygosity at all? Well, absence of recombination and segregation does make selection harder, we all know it from sex chromosomes. Gene conversion (or any force that homogenize haplotypes) can help fight this detrimental process as it was theoretically shown on Y chromosome. Maybe if the species starts homozygous already, the heterozygosity advantage is not so significant in contrast to benefit to avoid Muller’s ratchet by gene conversion. Obviously this is a superspeculation given my data; I would need some non-hybrid mitotic species or compare plenty of meiotic asexuals that are or are not of hybrid origin - the amount of available data is still bit limited. I suspect that with increasing number of asexual genomes sequenced we will soon find if this pattern fails as well or not.

Genome structure of polyploids

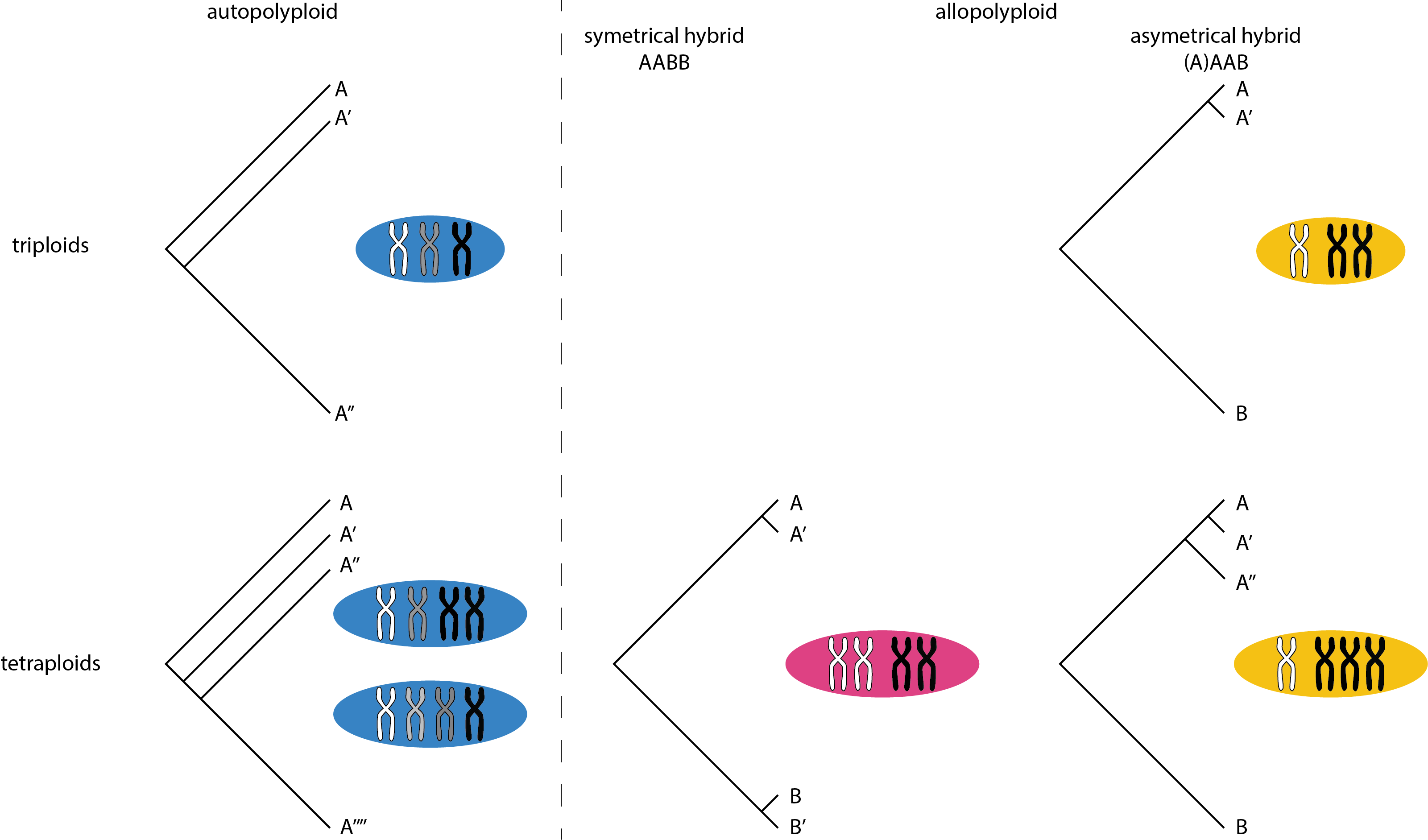

We also estimated different types of heterozygosity in the polyploid species. I though, that in autopolyploid (by whole genome duploication) one should expect an approximately event distribution of divergence between the three haplotypes, on the other hand allopolyploid species (of a hybrid origin) will display very uneven distribution with some of the chromosomes being closely related, “sexual like”, and some other being very diverged - those that have diverged during speciation. I charted this idea like this

Well, now let’s take a look what is the actual genome structure of polyploids in the dataset

Basically, rotifers must be of a hybrid origin (assuming my logic is correct). Meloidogyne are weird, but consistent - all of them have a single haplotype substantially diverged, but quite a lot of divergence between the other two or three haplotypes as well. It would be nice to have the genomes phased… The only Meloidogyne that stands out is floridensis. It have two almost identical haplotypes and a single diverged one (however far less diverged thatn in the cases of the other Meloidogyne). I would not be surprised if it would be of completely independent origin of asexuality (got to give credit to Dave Lunt for some of these thoughts). And finally with crayfish it’s hard to say. Since the variants are not phased it’s impossible to say if it’s one haplotype only diverged (in tetraploid case it’s surprisingly easier). I don’t know, what do you think. Is the crayfish a hybrid??

Summary

This study was a great fun for me. The only frustrating part I had was with collecting data (a previous blog about it), but in the end many of the authors actually fixed the data and/or uploaded them to databases, so in the end it was actually quite alright. While analyzing genomes I had a need to extend the available genome analysis tools by development of smudgeplot, which started a great great (still ongoing) collaboration with Rhyker.

I have three takehomes from this study and dicssions

- Never underestimate the role of hybridization (it’s everywhere and very impactful)

- The question “Can we very theoretical predictions about consequences of asexuality in natural populations?” is probably easy to answer - nope. If all the assumptions of the models are correct, none of the asexual lineages would exist. We could rather ask “What peculiarity is in this asexual lineage, so it could survive for millions of years?”

- Development of a bioinformatic tool is way easier if you do it for your dataset. Instead of showing a toy data I always showed the examples from my study and people immediately seen the point. I also feel it helped me tons with meeting amazing number of incredible people. Smudgeplots rulez!

There are couple more things I am considering to write about

- Genome structure of A. riciae - the very diverged haplotypes detected in the assembly can not be an artifact, the genome structure I detect either (I detect three peak kmer spectra with many many tetraploid loci) - all this suggest octoploidy but genome size measured by flow cytometry is just way too small.

- Super peculiar repetitive content of P. virginalis (probably unrelated to asexuality) and why do I think it’s of a hybrid origin too even there is a decade of literature speculating otherwise.

- more smudgeplots…

If you would be interested, let me know, it might help my motivation.

We used an extended version of GenomeScope for estimates of heterozygosity, Smudgeplot for estimates of ploidy and DNApipeTE to estimate transposons. I declare a conflict of interest - I am a developer of smudgeplot. ↩

Both Diploscapter species are actually unichromosomal organisms. ↩

Leave a Comment